The Story Of The Unknown Warrior

The British tomb of The Unknown Warrior holds an unidentified British soldier killed on a European battlefield during the First World War. He was buried in Westminster Abbey, London on 11 November 1920, simultaneously with a similar interment of a French unknown soldier at the Arc de Triomphe in France, making both tombs the first to honour the unknown dead of the First World War. It is the first example of a Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. The battlefield that the Warrior came from is not publicly known and has been kept secret so that the Unknown Warrior might serve as a symbol for all of the unknown dead wherever they fell.

The idea of a Tomb of the Unknown Warrior was first conceived in 1916 by the Reverend David Railton, who, while serving as an Army chaplain on the Western Front, had seen a grave marked by a rough cross, which bore the pencil-written legend 'An Unknown Soldier of the Black Watch'.

He wrote to the Dean of Westminster in 1920 proposing that an unidentified British soldier from the battlefields in France be buried with due ceremony in Westminster Abbey "amongst the kings" to represent the many hundreds of thousands of Empire dead. The idea was strongly supported by the Dean and the then Prime Minister David Lloyd George. There was initial opposition from King George V (who feared that such a ceremony would reopen the wounds of a recently concluded war) and others, but a surge of emotional support from the great number of bereaved families ensured its adoption. The War Graves Commission was instructed to create the National Site of Mourning to be dedicated on Armistice Day 1920.

It is to be noted however that a similar concept had been publicised in France during a public speech in November 1916 and that it was debated in Parliament by July 1918 and adopted in November 1919, before being enforced in November 1920.

Arrangements were placed in the hands of Lord Curzon of Kedleston who prepared in committee the service and location.

Suitable remains were exhumed from six principal battlefields - The Aisne, Marne, Cambrai, Somme, Arras and Ypres - and brought to the chapel at St Pol near Arras, France on the night of 7 November 1920. The bearer parties were immediately returned to their units and a guard placed on the door. At midnight Brigadier General L.J. Wyatt and Lieutenant Colonel E.A.S. Gell of the Directorate of Graves Registration and Enquiries went into the chapel alone. The remains were on stretchers, each covered by a Union Flag: the two officers did not know from which battlefield any individual body had come. General Wyatt with closed eyes rested his hand on one of the bodies. The two officers placed the body in a plain coffin and sealed it. The other bodies were then taken away for reburial. It seems highly likely that the bodies were carefully selected and it is almost certain that the Unknown Warrior was a soldier serving in Britain's pre-war regular army and not a sailor, territorial, airman, or Empire Serviceman.

The coffin stayed at the chapel overnight and on the afternoon of November 8, it was transferred under guard, with troops lining the route, from St Pol to the medieval castle within the ancient citadel at Boulogne. For the occasion, the castle library was transformed into a chappelle ardent: a company from the French 8th Infantry Regiment recently awarded the Legion d'Honoure en masse, stood vigil overnight.

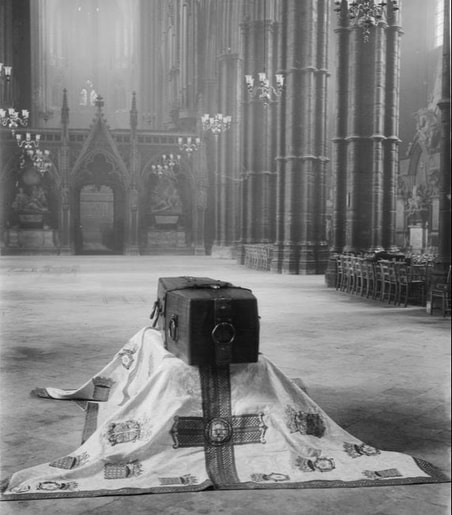

The following morning, two undertakers entered the castle library and placed the coffin into a casket of the oak timbers of trees from Hampton Court Palace. The casket was banded with iron and a medieval crusader's sword, chosen by the King personally from the Royal Collection, was affixed to the top and surmounted by an iron shield bearing the inscription 'A British Warrior who fell in the Great War 1914-1918 for King and Country'.

The idea of a Tomb of the Unknown Warrior was first conceived in 1916 by the Reverend David Railton, who, while serving as an Army chaplain on the Western Front, had seen a grave marked by a rough cross, which bore the pencil-written legend 'An Unknown Soldier of the Black Watch'.

He wrote to the Dean of Westminster in 1920 proposing that an unidentified British soldier from the battlefields in France be buried with due ceremony in Westminster Abbey "amongst the kings" to represent the many hundreds of thousands of Empire dead. The idea was strongly supported by the Dean and the then Prime Minister David Lloyd George. There was initial opposition from King George V (who feared that such a ceremony would reopen the wounds of a recently concluded war) and others, but a surge of emotional support from the great number of bereaved families ensured its adoption. The War Graves Commission was instructed to create the National Site of Mourning to be dedicated on Armistice Day 1920.

It is to be noted however that a similar concept had been publicised in France during a public speech in November 1916 and that it was debated in Parliament by July 1918 and adopted in November 1919, before being enforced in November 1920.

Arrangements were placed in the hands of Lord Curzon of Kedleston who prepared in committee the service and location.

Suitable remains were exhumed from six principal battlefields - The Aisne, Marne, Cambrai, Somme, Arras and Ypres - and brought to the chapel at St Pol near Arras, France on the night of 7 November 1920. The bearer parties were immediately returned to their units and a guard placed on the door. At midnight Brigadier General L.J. Wyatt and Lieutenant Colonel E.A.S. Gell of the Directorate of Graves Registration and Enquiries went into the chapel alone. The remains were on stretchers, each covered by a Union Flag: the two officers did not know from which battlefield any individual body had come. General Wyatt with closed eyes rested his hand on one of the bodies. The two officers placed the body in a plain coffin and sealed it. The other bodies were then taken away for reburial. It seems highly likely that the bodies were carefully selected and it is almost certain that the Unknown Warrior was a soldier serving in Britain's pre-war regular army and not a sailor, territorial, airman, or Empire Serviceman.

The coffin stayed at the chapel overnight and on the afternoon of November 8, it was transferred under guard, with troops lining the route, from St Pol to the medieval castle within the ancient citadel at Boulogne. For the occasion, the castle library was transformed into a chappelle ardent: a company from the French 8th Infantry Regiment recently awarded the Legion d'Honoure en masse, stood vigil overnight.

The following morning, two undertakers entered the castle library and placed the coffin into a casket of the oak timbers of trees from Hampton Court Palace. The casket was banded with iron and a medieval crusader's sword, chosen by the King personally from the Royal Collection, was affixed to the top and surmounted by an iron shield bearing the inscription 'A British Warrior who fell in the Great War 1914-1918 for King and Country'.

The casket was then placed onto a French military wagon, drawn by six black horses. At 10.30 am, all the church bells of Boulogne tolled; the massed trumpets of the French cavalry and the bugles of the French infantry played Aux Champs (the French "Last Post"). Then, the mile-long procession - led by one thousand local schoolchildren and escorted by a division of French troops - made its way down to the harbour.

At the quayside, Marshal Foch saluted the casket before it was carried up the gangway of the destroyer, HMS Verdun (L93), and piped aboard with an Admiral's call. The Verdun slipped anchor just before noon and was joined by an escort of six battleships. As the flotilla carrying the casket closed on Dover Castle it received a 19-gun Field Marshal's salute. It was landed at Dover Marine Railway Station at the Western Docks on 10 November and was taken ashore to a train by a bearer party of six Warrant Officers from the Royal Navy, the Royal Marines, the Army and the Royal Air Force and escorted by two Generals, two Admirals and two Air Marshalls.

The coffin then was carried to London in South Eastern and Chatham Railway General Utility Van No.132, which had previously carried the bodies of Edith Cavell and Charles Fryatt. The van has been preserved by the Kent and East Sussex Railway.

The train went to Victoria Station, where it arrived at platform 8 at 8.32 pm that evening and remained overnight under escort of the 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards. (A plaque at Victoria Station marks the site: every year on 10 November, a small Remembrance service takes place between platforms 8 and 9.)

The following morning, 11 November 1920, the casket, covered with the Union Flag, on which was placed a steel helmet and side-arms, was placed onto a gun carriage of the Royal Horse Artillery drawn by six horses and led by a Firing Party and the Regimental bands of the Brigade of Guards, set off through immense and silent crowds. As the cortege set off, a further Field Marshal's salute was fired in Hyde Park. The route followed was Hyde Park Corner, The Mall, and to Whitehall where the Cenotaph, a "symbolic empty tomb", was unveiled by King-Emperor George V.

At the Cenotaph, the carriage halted and KingGeorge placed a wreath of roses and bay leaves (the Poppy Appeal did not begin until 1921) on the coffin.

At the quayside, Marshal Foch saluted the casket before it was carried up the gangway of the destroyer, HMS Verdun (L93), and piped aboard with an Admiral's call. The Verdun slipped anchor just before noon and was joined by an escort of six battleships. As the flotilla carrying the casket closed on Dover Castle it received a 19-gun Field Marshal's salute. It was landed at Dover Marine Railway Station at the Western Docks on 10 November and was taken ashore to a train by a bearer party of six Warrant Officers from the Royal Navy, the Royal Marines, the Army and the Royal Air Force and escorted by two Generals, two Admirals and two Air Marshalls.

The coffin then was carried to London in South Eastern and Chatham Railway General Utility Van No.132, which had previously carried the bodies of Edith Cavell and Charles Fryatt. The van has been preserved by the Kent and East Sussex Railway.

The train went to Victoria Station, where it arrived at platform 8 at 8.32 pm that evening and remained overnight under escort of the 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards. (A plaque at Victoria Station marks the site: every year on 10 November, a small Remembrance service takes place between platforms 8 and 9.)

The following morning, 11 November 1920, the casket, covered with the Union Flag, on which was placed a steel helmet and side-arms, was placed onto a gun carriage of the Royal Horse Artillery drawn by six horses and led by a Firing Party and the Regimental bands of the Brigade of Guards, set off through immense and silent crowds. As the cortege set off, a further Field Marshal's salute was fired in Hyde Park. The route followed was Hyde Park Corner, The Mall, and to Whitehall where the Cenotaph, a "symbolic empty tomb", was unveiled by King-Emperor George V.

At the Cenotaph, the carriage halted and KingGeorge placed a wreath of roses and bay leaves (the Poppy Appeal did not begin until 1921) on the coffin.

After the two-minute silence, the gun carriage continued to Westminster Abbey followed by the King, the Royal Family and ministers of state. Outside the Abbey and flanked by a guard of honour of one hundred recipients of the Victoria Cross, the coffin was borne by NCOs from the Brigade of Guards into the West Nave. The funeral service consisted of music from only English composers.

At the conclusion of the last hymn, the helmet and sidearms were removed and the coffin laid in the tomb. The King scattered earth from a silver shell case and the Victoria Cross holders filed past either side of the grave. The service was the mourning of the nation. The honours that had been paid were those due to a Field Marshall.

The guests of honour were a group of about one hundred women. They had been chosen because they had each lost their husband and all their sons in the war. "Every woman so bereft, who applied for a place got it".

At the conclusion of the last hymn, the helmet and sidearms were removed and the coffin laid in the tomb. The King scattered earth from a silver shell case and the Victoria Cross holders filed past either side of the grave. The service was the mourning of the nation. The honours that had been paid were those due to a Field Marshall.

The guests of honour were a group of about one hundred women. They had been chosen because they had each lost their husband and all their sons in the war. "Every woman so bereft, who applied for a place got it".

|

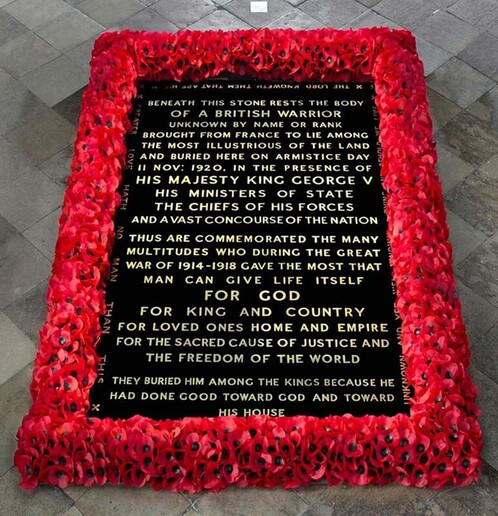

The grave was capped with a black Belgian marble stone (the only tombstone in the Abbey on which it is forbidden to walk) featuring this inscription, composed by Dean Ryle, Dean of Westminster, and engraved with brass from melted down wartime ammunition.

The stone's inscription reads:- BENEATH THIS STONE RESTS THE BODY OF A BRITISH WARRIOR UNKNOWN BY NAME OR RANK BROUGHT FROM FRANCE TO LIE AMONG THE MOST ILLUSTRIOUS OF THE LAND AND BURIED HERE ON ARMISTICE DAY 11 NOV: 1920, IN THE PRESENCE OF HIS MAJESTY KING GEORGE V HIS MINISTERS OF STATE THE CHIEFS OF HIS FORCES AND A VAST CONCOURSE OF THE NATION THUS ARE COMMEMORATED THE MANY MULTITUDES WHO DURING THE GREAT WAR OF 1914 - 1918 GAVE THE MOST THAT MAN CAN GIVE, LIFE ITSELF, FOR GOD FOR KING AND COUNTRY FOR LOVED ONES HOME AND EMPIRE FOR THE SACRED CAUSE OF JUSTICE AND THE FREEDOM OF THE WORLD THEY BURIED HIM AMONG THE KINGS BECAUSE HE HAD DONE GOOD TOWARD GOD AND TOWARD HIS HOUSE |

Text is taken from the British Legion website